- Home

- / Blog

- / Art History

Four Pandemics - Four Interpretations of Art

12/07/2021

In March of 2020, as authorities told the world to batten down the hatches and wait out the novel Coronavirus, creatives were buoyed by the idea that plagues create fantastic works of art. Shakespeare's King Lear and Boccaccio’s Decameron stand as prime examples of plague-inspired art. It is not a pandemic, however, that inspires. Many, including this artist, will claim that disease and destruction may correlate with an absence of inspiration. Perhaps the slow art market also agrees. Upon closer inspection, King Lear (or HBO's Succession) tells us don’t trust your kids; from history we know that plague times are a real downer, and the art is downright frightful. But disease is not the determining factor contributing to strokes of genius. Instead, art and inspiration comes from the human desire to make sense of an invisible enemy and come to terms with what lies ahead in the hereafter. No three-dimensional model of a viral vector can evoke the same feelings as Pieter Breughel the Elder’s Triumph of Death or even Edvard Munch’s Self-Portrait with the Flu.

Did Pieter Breughel the Elder outsmart death?

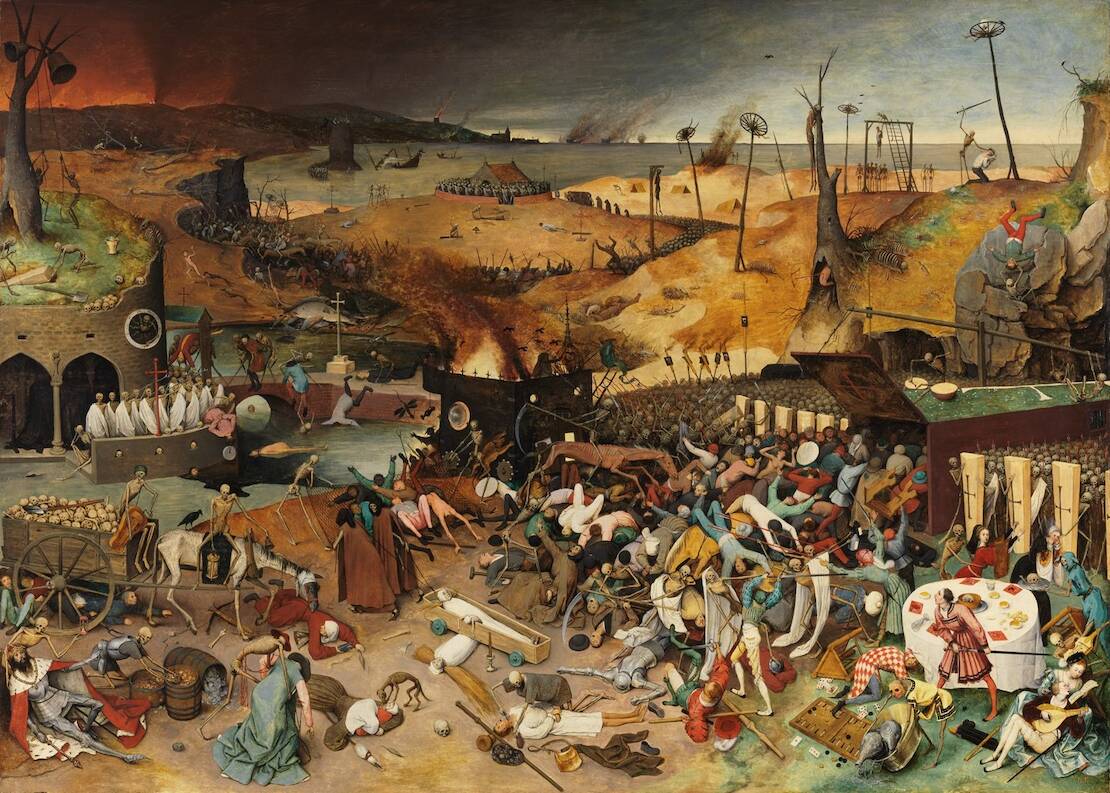

When considering art made during a pandemic, it is impossible to forget the specter of plagues over the early modern period. The Black Death decimated generations of Europeans and, like today's pandemic, spared no one. Pieter Breughel created a depiction of destruction too realistic to forget. Even in today's world of bleaching agents and modern medicine, it is impossible to come away from the report without it making an impact. Breughel painted a red and sepia atmosphere that is so evocative it reeks of brimstone. Long attenuated figures lie in a heap in the foreground, and smoke ripples just offshore in the background. Not religion, nor academia, nor the power of armies can stop the destruction of death. Many of the figures are silently resigned to their hellish end and perhaps eternity. In the lower right corner are a pair of lovers, unconcerned by the current scene, which will inevitably be smite-ed by the same wrathful death impacting the rest of the scene.

Pieter Breughel the Elder, The Triumph of Death, c.1562 via Wikimedia

Hans Holbein the Younger, Danse Macabre, 1523-25,

woodcut, via Wikimedia.

This chaotic scene follows the great Northern Renaissance tradition known as The Dance of Death (or la Danse Macabre). This dark theme has been prevalent since the Middle Ages, a time marked by short, violent, dirt-sucking lives. Death is the great uniter. No matter one's life station, eventually, death will take everyone. A personification of death, often a skeletal figure, dances cheerfully as an often-gory end meets the rest of the figures in the scene. Hans Holbein is famous for his woodcuts depicting a skeleton representing death comically interacting with all manner of people from priests to fools. While decidedly cartoonish, this theme serves a purpose as a memento mori. Death becomes everyone; Christianity drives this concept home through the death of Christ—ashes to ashes, dust to dust. This reminder by Breughel is expressive enough to continue expressing a message of death conquering all centuries later. While Breughel the Elder died like any man, his art has become an immortal signifier.

Why does Breughel’s style seem so Familiar?

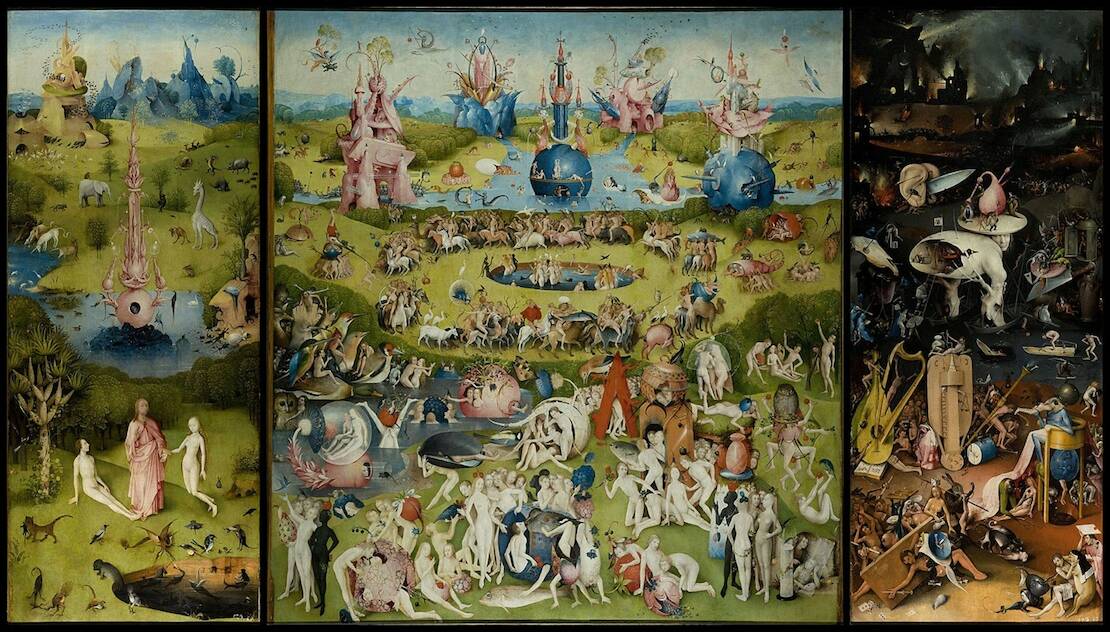

Three adjectives define Early Modern and Renaissance Northern Art: dark, sad, and frightening. While these words could apply to the style of clothing found in portraits, replete with buckled shoes, pointy hats, and neck ruffs, it comes across in all the art, especially religious scenes. While southern Europe, namely Italy, Spain, and France, were consumed with the Papacy and a style of worship connected with religious imagery, the North began to take a step away from the idols. Religious imagery was no longer cinematic and narrative like Italian Frescoes or even French stained-glass windows. Although, the art still served a purpose, a didactic warning of what lay ahead for those who obeyed or did not. The artist who determined this style was Hieronymus Bosch. He is most well-known for the Triptych altarpiece known as The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 via Wikimedia.

Bosch depicts a possibility in each panel, including paradise and hell on the side panels, and the middle gives the work its name, showing the delights one might indulge in their earthly life or perhaps abstain. However, what is notable about this work is that while hell is frightening, earth and paradise do not offer better alternatives. Long, pointy creatures haunt the entire piece, some seem human, but others seem entirely alien. The figures seem like something out of Dr. Seuss if his characters went to Burning Man and never came down from their high. It is frightening and odd all around. The points, thin line work, and overall effect of the painting are not unlike Breughel's work, which is not a mistake. Look at the slender pointy boats in the background or the writhing bodies in the foreground; it is unmistakable. Bosch was the teacher of Breughel, and art history believes that the student eventually surpassed the teacher. While Bosch's viewpoint of heaven is tepid at best, while Breughel seems to take a much more fire and brimstone approach, perhaps this owes to Breughel’s success.

Did the Pandemic Impact Art in Southern Europe?

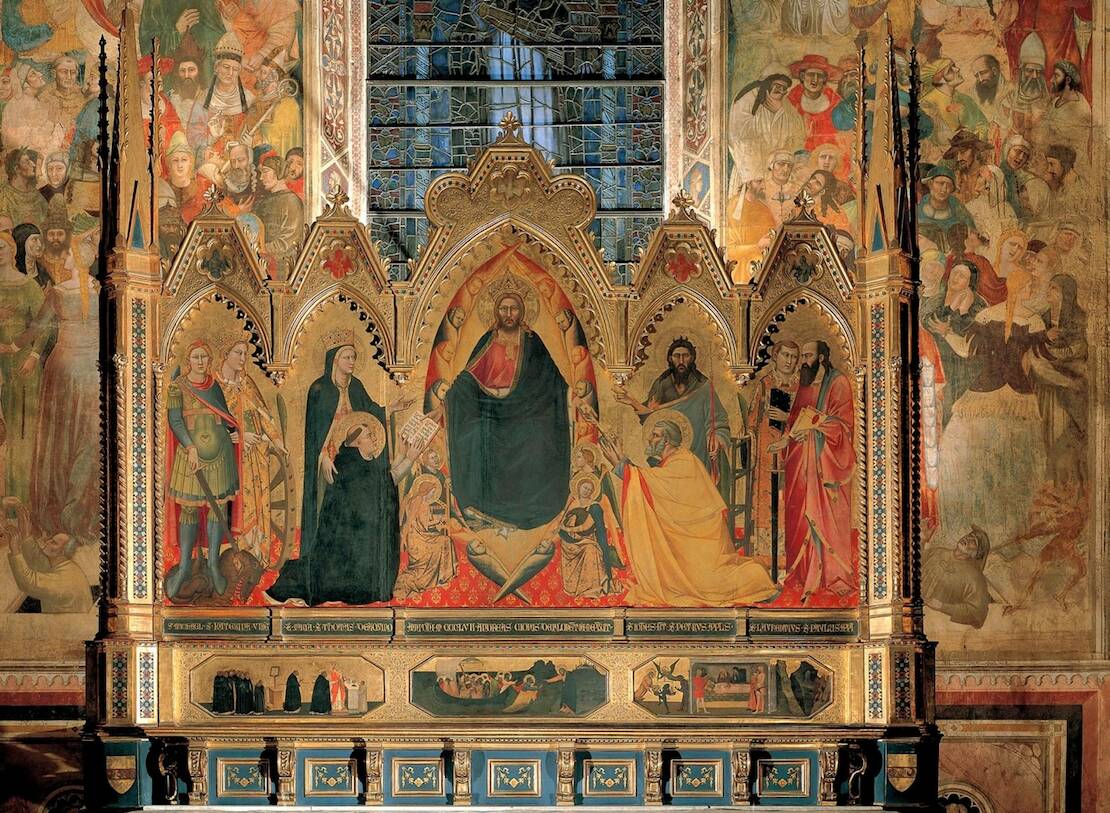

Italy was not in a vacuum and experienced the same destruction during the medieval period as the rest of Europe. Giovanni Bocaccio memorialized the reaction to the Black Death in Italy in The Decameron, which tells the story of ten young people holed up in a villa just outside Florence during the pandemic in Italy. The Black Plague changed the landscape of art and storytelling, a critical factor in this type of art. In many ways, art contemporary to the Black Plague saw a step backward and reliance upon earlier styles. A profound example in Florence's Santa Maria Novella is the Strozzi altarpiece in one of the side chapels. It looks like a typical altarpiece to the uninitiated viewer, but to the trained eye, it seems almost entirely out of its time.

Andrea Orcagna, Strozzi Altarpiece, 1354-57, tempera on wood, via Wikimedia.

His contemporaries lauded Andrea Organa's design. Many were excited by its similarities to Giotto, the artist with what was considered a pure approach. Modern art historians have even dug deeper into the historical canon, comparing the outlining in the piece to mosaics of Justinian. There is a theme that involves exploring the past. Little did Organa and his contemporaries know that the Zenith of Italian Art was yet to come. Reliance on the past comes out in times there is an uncertain future such as the gruesome Bubonic Plague. It is easier to speak in grandiose terms of salvation than to cope with the idea that death is not only universal but imminent.

What about more recent pandemics like the Spanish Flu

The pandemic most contemporary to the Coronavirus is the Spanish Flu of 1918. As the concept of a current pandemic takes shape, many look to the Spanish Flu as a guide. The art of this period is also evocative of the suffering that feels tangible to the contemporary viewer. Artist Edvard Munch created his work, Self-portrait After Spanish Flu, 1919, in response to his battle with the infection. While he saw the enemy take a course through his own body and live to tell the tale, there is a level of uncertainty that comes along with a plague infection, even one that has healed. The illness's immediate effects are apparent, but what about the long-term impacts that lurk beneath the surface to expose themselves later?

Munch, Schiele, and Dada

Even for non-fans of art, Munch's Scream is an artwork almost everyone recognizes. Perhaps it is how tangible the emotions are that come forth from the canvas? Everyone knows the feeling of de-centeredness the figure expresses as he screams with hands on the side of his face. It is not by mistake that the movement Munch belongs to is the Expressionist movement. He brings the same tangible feelings to his self-portrait. In the painting, Munch depicts himself sitting in his living room, hunched in a chair, and sallow with the aftereffects of the illness. The lurid green and acidic yellow used widely across the canvas add to this impact. The artist's figure is alive but empty with little expression, and the impression the painting gives is of unwellness. The existential drama the artist was famous for embodying came to life in his physical experience.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with Spanish Flu, 1919 via Wikimedia.

.Munch was not alone in this phenomenon either many other artists also fell ill with the Spanish Flu and depicted themselves in the throes of illness. For example, Egon Schiele drew his teacher Gustav Klimt on his deathbed and not much a later a picture of his pregnant wife, Edith, on her deathbed. The artist died three days later, aged 28, and with his demise, a dream for a family dashed. Yet, not long after losing Klimt, he painted a family portrait with his wife and a swaddled babe at their feet. History regards Schiele for his edgy and potentially transgressive pictures of nude, female bodies. Yet, in the face of massive tragedy, even the provocateur became nostalgic.

Egon Schiele, Die Family, 1918, via Wikimedia.

What does this mean for art today?

When faced with unfathomable amounts of death and destruction, innovation and exploration seem nearly impossible, if not an entire waste of time. Quickly, the atmosphere becomes existential and sentimental, which leaves little room for revelation. However, the destruction does leave space for reflection and reevaluation. This pattern repeats through generations of illness and paradigm shifts. As the human race's culture appears on the razor's edge of destruction, an expression of creativity must memorialize the watershed moment. For centuries, this meant turning back to religion and considering such a disaster's ontological ramifications. Breughel and Bosch depicted fiery, tragic, fear-inducing options for the hereafter, perhaps in a desperate hope to hang on to them now. In both depictions, the most appealing aspects lie within earthly delights. The world is ending, but the lovers continue, and Bosch's creatures cavort.

In the Middle Ages, academics brought art back to the lowest common denominator, religion. Christ offers eternal life to his followers, and a reflection upon early Christian art reflects the simple message. Even in the 20th-century, artists reflected upon their mortality and their role in the course of human history. Instead of focusing on high-minded and theological philosophies, their approach was far more personal, simply planting a flag in the ground and saying I existed, my family lived. Art following 1918 got increasingly high-minded and almost goofy, as little could matter after losing so many lives to disease and war. Dadaism was a direct response to the pain, and it isn't surprising that a urinal acted as a stand-in for the virgin Mary. In the context of so much loss, an empty, false idol seemed to be the only natural way to taunt death.

How the current art scene chooses to approach the grief of the most recent pandemic remains to be seen. Sometimes it seems as though the severe reflection escaped to a world of far-fetched and silly creations. As our loved ones suffer, we watch a documentary about wild hillbillies who keep tigers in their back yard or look on as Kardashians take over the world with utter fascination. Perhaps as the pandemic recedes into the collective memory as part of history, rather than a present emergency, a solid narrative will emerge, or perhaps not? Maybe making endless banana bread is an artistic meditation in and of itself.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Nicole Lania is an art historian and writer who has years of experience finding genuine creativity in a world of thinly veiled reproductions. She earned a master’s degree from New York University with a focus on contemporary art and writing; her thesis was on the impact Christo’s The Gates had on the cultural capital of Central Park and the surrounding neighborhoods. She can be found walking her dog, Tucker through the New England wilderness or baking pastries in her kitchen. Nicole can be found on Instagram @nik.lania, Twitter @NicoleLania1, or her website http://www.nicolelania.com/.

Bibliography

Christian Iconography. n.d. Orcagna (Andrea di Cione), The Strozzi Altarpiece. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.christianiconography.info/Florence/Santa%20Maria%20Novella/christDominicPeterOrcagna.html.

Kambhampaty, Anna Purna. 2020. How Art Movements Tried to Make Sense of the World in Light of the 1918 Pandemic. May 5. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://time.com/5827561/1918-flu-art/#:~:text=Norwegian%20painter%20Edvard%20Munch%20also,contracting%20and%20surviving%20the%20illness.

Kirsch, Andrea. 2020. During the Spanish Flu Existential Paintings by Edward Munch and Egon Scheile. June 22. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.theartblog.org/2020/06/during-the-spanish-flu-existential-paintings-by-edward-munch-and-egon-schiele/.

Prado Museum. n.d. Garden of Earthly Delights. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.afpradomuseum.org/the-garden-of-earthly-delights-bosch/history?gclid=Cj0KCQjwreT8BRDTARIsAJLI0KKXGz0kuVoNmyfsFCFLOwZfDKSF5BqsnXdRjT3x2cQ9T_e_FJ4E2CIaAvDPEALw_wcB&gclid=CjwKCAjwoP6LBhBlEiwAvCcthKQGSV4LZbT0GIWyOX0TYEPmw0q5BF60N5F6QFucd1MDrujrvI0.

—. 2015. The Triumph of Death. April 28. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-triumph-of-death/d3d82b0b-9bf2-4082-ab04-66ed53196ccc.

Smith, Karen Sue. 2017. Bosch and Breughel: From Monstrous to Ordinary. April 24. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.americamagazine.org/arts-culture/2017/04/24/bosch-and-bruegel-monstrous-ordinary.

Wikipedia. 2021. Danse Macabre. October 28. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danse_Macabre.