- Home

- / Blog

- / Art History

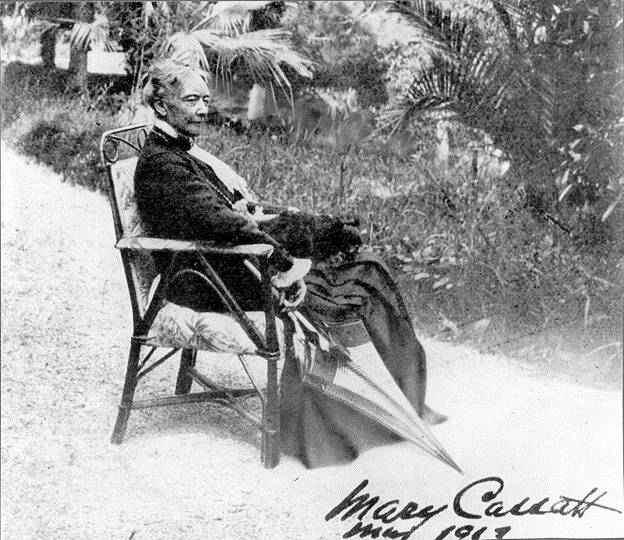

Mary Cassatt - Artist and Activist

09/11/2021

Successful, well-traveled, and highly-educated feminist artist Mary Cassatt was born in 1844. She is today seen as being one of the few American artists to have played an active role in the French avant-garde movement. She is also known for her impressionist paintings that often depict the intimate bond between mothers and their children. Ironically enough, Cassatt never married or had children. With that said, one can agree that she makes for a rather curious figure to study.

Mary Cassatt's Early Years

American Impressionist painter Mary Stevenson Cassatt was born in what is today a part of Pittsburgh, PA. Cassatt was born and raised in an upper-middle-class background. Her mother came from a family of bankers and her father was a stockbroker. Her family believed travel to be an integral part of education. She was thus a well-traveled young lady who visited Berlin, London, and Paris in her youth. She spent five years in Europe as a child and learned French and German during her time there. Travel was also one of the major factors that facilitated her interest in art and painting. Perhaps it was at the Paris World’s Fair in 1855 that Cassatt was first exposed to French art and artists.

.jpg)

At the age of 15, Cassatt began studying art in a formal capacity at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. One-fifth of the class was comprised of female students and while most of them looked at the ability to create art as a valuable social skill, Cassatt’s aspirations lay elsewhere. She wanted to become a professional artist.

Uninspired by the teaching style and the slow pace of the curriculum, and fed up with the generally condescending attitude towards female students, Cassatt wanted to move back to Paris, which was the center of the modern art world. She was convinced that she would learn much more in Europe, where she could study the works of Old Masters firsthand. She had to convince her parents to let her travel, since traveling across the pond in the nineteenth century for the sake of one’s professional growth was not a rather common occurrence. Though her father announced that he’d rather see his daughter dead than living abroad as a bohemian, they finally gave in to her requests. Cassatt moved to Paris with her mother and some family friends in 1866.

1851, Wikimedia Commons.

Now a young determined lady in Paris, Cassatt applied to study with masters from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts since women weren’t allowed to take classes at the school. She took private lessons from academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme here. Soon after, she joined a painting class taught by genre artist Charles Chaplin. She also studied with Thomas Couture. She plunged herself into painting and in 1868, her work The Mandolin Player (painted by her as “Mary Stevenson”) was accepted to the Paris Salon, an exhibition run by the French government.

Soon after, though, due to the Franco-Prussian war, she had to go back to the U.S. for a brief stint. She felt as though her wings had been tied. It didn’t help that her father outright refused to pay for her art supplies. She tried to sell her paintings in New York but to no avail - she found many admirers but no buyers for her work. Then when not more could go south, in 1871, her paintings burnt in a fire in Chicago.

By this point, she felt rather defeated and was desperate to return to Europe. And she did! In 1971, she was contacted by the Archbishop of Pittsburgh. He commissioned her to paint copies of paintings in Correggio, Parma in Italy. Safe to say, she immediately left for Europe.

In Italy, she spent eight months studying under the tutelage of Carlo Raimondi, head of the department of engraving at the Parma Academy. Her paintings were also accepted by the Paris Salon in 1872, 1873, and 1874. Now, an established artist in the European art scene, she settled down in Paris and began traveling to parts of Italy, Spain, and Belgium to paint.

Cassatt and Impressionism

Yes, Mary Cassatt was now doing well as an artist. However, she also began to feel increasingly constrained in her vision. She did not like to be bogged down by guidelines - she wanted to be free in her artistic expression.

She began using bright colors to draw, became inspired by the new wave of artists, and began to reclaim her vision as an artist. It felt good; she felt free.

via Wikimedia Commons.

Renowned impressionist painter Edgar Degas was one of Mary Cassatt’s major influences. And it was Degas, impressed by Cassatt’s ability to capture a moment in time, who invited Cassatt to join the progressive art movement of independent artists known as impressionism in 1979. Degas and Cassatt went on to maintain a friendship that lasted a lifetime, with Degas also mentoring Cassatt.

Impressionism is the art movement that depicts nature and human life caught in time. Impressionist artists are not all that interested in portraying the lives of great men or mythological events. They were interested in painting the impression of what they saw instead of landscapes, people, and things around them. They explored different ways of painting and representing reality the way they saw it.

Mary Cassatt, along with French impressionist artists, experimented with bright colors, loose brushstrokes, and unique viewpoints. Much like Degas, Cassatt was also primarily interested in figure compositions.

She quickly gained attention as one of the most prominent Impressionist painters. So much so that the artist has been described as being one of the “Les Trois Grandes Dames” (the three great ladies) of Impressionism by Parisian journalist and art critic Gustave Geffroy. The other two women in this power triad are French artists Berthe Morisot and Marie Bracquemond.

In her painting titled “The Cup of Tea” 1880-81, Mary Cassatt used her sister, Lydia Cassatt, as a model and showed her partaking in drinking a cup of afternoon tea, a common social ritual amongst upper-middle-class women.

Initially, Cassatt drew inspiration for her paintings from her friends and family. However, an exhibition in 1890 became a game-changer. The exhibition of Japanese woodblock prints influenced her to move away from form to line and pattern. She employed techniques such as drypoint and aquatint to perfect her printmaking technique.

It was post-1890 that the dominance of mothers as caregivers with their children established a strong motif in her art works - the motif that has become so closely associated with Mary Cassatt’s works today.

“Young Mother Sewing” by Mary Cassatt, 1900, is one of two thousand works of art collected by feminist Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer and her children and donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art as part of the Havemeyer legacy.

The 1890s was a busy time for Cassatt. She painted many of her most well-known paintings, became a feminist role model for many young Americans and women artists. She also began to advise major art collectors, especially collectors of American art. In 1901, she consulted Mr. and Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer and accompanied them on an art-buying trip to Italy and Spain. She played a crucial role in shaping Havemeyer’s famous art collection, much of which can today be found at the MET in New York City.

_by_Mary_Cassatt,_Huntington_Library.jpg)

In 1895 her painting, The Boating Party, was the central piece in a solo exhibition of Mary Cassatt's work staged in the United States. This painting is a bold composition featuring simplified colors and unusual angles influenced by her studies of Japanese prints which were a potent force of influence on the Impressionists in Paris in the 1890's.

Due to her failing eyesight and other health concerns (diagnosed in 1911), Cassatt’s ability to create was affected. She eventually had to give up painting entirely in 1914. She did, however, continue to fight for women’s rights, becoming a rather active part of the movement. In 1915, she showed eighteen of her works in an exhibition supporting women’s suffrage.

Cassat passed away in her country home in Mesnil-Theribus in France in 1926 - unmarried, childless, and hugely accomplished.