Princess of Polka Dots

03/28/2021

Picture it, Manhattan 2013. It is nearly Thanksgiving, and you find yourself on West 19th bundled up in the Meatpacking District, stamping your feet to keep warm in a line of people snaking all the way around to 10th Avenue. If you had your druthers, this is not the most charming corner of town where you would loiter. It stinks, literally, not exactly the ambiance of an art gallery. The odor is due in part to the nearby water treatment center and meatpacking plants—fancy. If you are smelling death and decay, you know you are in the right spot. However, today you are not morose. You do not growl at passersby or complain that your toes might be frostbitten. You stand on the corner with bated breath because you know something exceptional waits just around the corner, Kusama’s installation.

Art of the Infinite

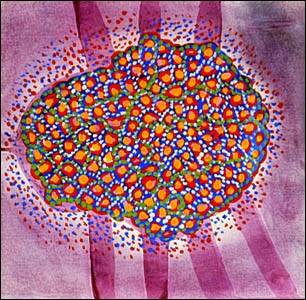

Yayoi Kusama, the Japanese artist created an infinity mirror room, Love is Calling, at the famed David Zwirner Gallery. When you enter, you leave the stinky, frigid reality of a late-fall Manhattan street and escape elsewhere. The lights are neon, there are mirrors on all sides, and thousands of polka dots decorate the room. This is Yayoi Kusama's installation. You might try to snap a selfie, but it will never be quite right; the neon lighting creates a shimmering haze and there are infinite reflections and refractions happening around you. Like a casino, you could easily spend hours in the room without realizing it. You are snapped out of your trance by a waifish gallerist dressed in black. They are surprisingly powerful for petite young women, and, before you know it, you are outside of the gallery. If not for the cold air, you would still feel floaty and dazed. And what's more, the only thing you can see is polka dots.

.jpg)

So What Exactly Is An Infinity Room?

If Kusama's artwork were capitulated in a single word, that word would be infinity. Why not polka dots, you ask? While the dots are essential, they are a symbolic stand-in for infinity. How Yayoi Kusama experiences consciousness is unique. While the average person will notice the objects in their surroundings or if it is light or dark or maybe the temperature or the smell of the room, most will only take note of a few of those details. For Kusama, she experiences all the things listed above and more. On top of all the information our senses give a person about their reality, she also hallucinates polka dots. She uses the infinity room or net to describe this. The polka dots immerse her entire existence, similar to the funhouse effect created by mirrors reflecting against each other. The dancing lights in her rooms remove the viewer from their own reality. Polka dots loom so mainly in her reality that sometimes she loses the concept of depth or time. Imagine infinite space. An infinity net creates a similar effect but with netting that encapsulates the viewer rather than reflecting them in a mirrored room.

Read also: Five Illuminating Facts About Dan Flavin

The Obliteration of Nothingness

Sometimes, Kusama explores the concept of infinity with the opposite approach. In her obliteration rooms she explores infinity as an idea rooted in nothingness. The dots pile up on an otherwise pristine white room and cancel each other out. Dots which would hold their own space within an infinity room, collapse together in the obliteration rooms. They take up space and they exist to a point where it is hard to decipher what is a dot and what isn’t one. The room has become both dot-filled and without dot forms all at once. The polemic of infinity is important because it does not just represent everything, it also represents nothing.

The Obliteration Room, photo by Stephan Ridgeway via Wikimedia Commons

This concept repeats across her entire oeuvre, in paintings, drawings, illustrations of popular children's stories, soft sculptures, and even pumpkins. The polka dot is the modality she uses to describe her experience to the world. The Tate Museum, London has even deemed her the Princess of Polka Dots.

Read also: Inside The Borderless World of TeamLab

In The Beginning, There Were Polka Dots

In the context of her painting Flower (D.S.P.S), she explains how the polka dot hallucinations started. In her childhood home, she sat doodling and spacing out as ten-year-olds do. When she looked up from the red, floral tablecloth, the red dots she was focusing on were everywhere. They were on the wall, the floor, the ceilings, and even the stairs. Space and time collapsed into a singular polka dot-based reality. It was such a vivid hallucination that she couldn't capture the depth when young Kusama climbed the stairs. However, this was not a simple childhood mishap like spinning in too many circles and getting dizzy. The dots never stopped appearing to Kusama. While others might take this on the chin and abandon their life plan, she made polka dots her greatest strength, and the polka dots act as what she calls her "way to infinity."

Did Polka Dots Define A Revolution?

In the hands of Yayoi, bona fide polka dot royalty, polka dots percolated with power. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Kusama became fascinated with the re-imagined landscape of American counter-culture. New York was the east coast outpost for countercultural happenings, while the west had San Francisco. The Fillmore, a popular counterculture venue, had two locations: one in New York's East Village and another in San Francisco's eponymous Fillmore neighborhood. Drawn to the happenings of hippies and protests, she moved to New York City. Kusama even performed at Fillmore East with Fleetwood Mac.

The psychedelic colors of the sixties pulse as if on an electric charge in Flower D.S.P.S. and certainly pulsed in the light shows Yayoi set up for musicians and audience alike to immerse themselves, obliterating sensory divisions between individual beings, light, and sound.

Metaphoric Mappings: Symbols of Trauma

in Polka Dots, 1968 via Pinterest

Against the backdrop of free love and good vibes, polka dots might appear equally light-hearted and straightforward. However, as with so many artists, Kusama's dots belie something darker, textured, and traumatic. Her work in the 1960s plays with the tensions between ditzy patterns and a dark personal history seeking resolution as dotted delusions.

Yayoi grew up in a well-to-do family of Japanese seed merchants. Rather than embodying the simple beauty of the flowers her family sold, Yayoi's childhood was unstable. Parental figures in Kusama's life were not evergreen. She was subject to not only emotional neglect but abuse.

Kusama's father was a cad, or worse. He was never present and chased anything with a skirt, including the household staff. Her mother was distraught by his philandering. Rather than focusing her attention on Yayoi as a child needing love, her mother chose to engage with his craziness. When Yayoi expressed interest in the arts, her parents stifled her dreams. Some say they went as far as tearing up Kusama's artwork.

Growing up in this pressure-cooker situation, it is not shocking that Yayoi experiences mental illness. The mind can only take so much trauma and neglect. In service of protecting her, perhaps her subconscious brought about polka dots as a coping mechanism.

Once she began making artwork in New York, the scars of her youth were laid bare. As a protest to the Vietnam War, Kusama would pose coquettishly in public spaces such as the Brooklyn Bridge or Central Park. In these situations, she was photographed nude, with a kittenish smirk, surrounded by polka dots. Sometimes if her exhibitions happened in public, she chose instead to wear a polka dotted leotard. Her play with the female form belies larger issues within her biography. Yayoi Kusama admits that she fears men. Her father's misogyny and abusive behavior broke a forgotten child. It only seems appropriate for her to question male authority as well as culturally ingrained misogyny.

But while she examines male motivations, she does not hate men. Some of her most ardent supporters are her male colleagues, including Frank Stella and Donald Judd. She had close platonic relationships with artists Andy Warhol and Joseph Cornell. After Cornell's death, she fell into a deep depression, which resulted in a return to Japan.

Polka Dot Metabolism

When Kusama returned to Japan in the early 70s, she was very ill. She had become grief-stricken following her close friend's death and was getting backlash for her nude artwork. Her family believed that the nudity was disrespectful.

In return, Kusama experienced feelings of shame. Shame teamed with deepening depression lead to a suicide attempt. So, when she returned to Japan, she checked herself into the hospital and still lives there today. She keeps a studio a few blocks from the hospital and will take occasional business trips abroad when her dancing LED displays necessitate travel.

During the early days of her hospitalization, she wrote novellas, short stories, and other texts with a surrealist tilt. Polka dots remained an extensive aspect of her work, even within the writing.

She strips herself bare and processes her experiences. At first glance, it would appear as though her insanity drives her fame and genius. However, this is too easy, a logical trap. While she certainly does experience mental illness and enjoys a medical institution's relative stability and safety, she is not insane. Art is the way that she integrates and metabolizes her condition. Her artworks are a method to work through her experiences.

The fact that she shares her artwork with the world is mind-blowing. It would be like someone sharing a diary or the notes app (please don't read my unfortunate, handwritten book).

That certainly does not sound like the works of a madwoman; although, given the polka-dotted subject matter, it can be easy to conflate brilliance and illness. She comes across as a grounded, sane individual. She enjoys Godiva chocolates and wearing her hair just so—very human traits. It just so happens she also sees dots all the time. No one can help some of life's circumstances, but they can face them every day. Kusama faces her reality every day. The stunning installations she creates are unique and brilliant because she is all these things, and she is, most importantly, more than her illness.

Read also: Princess of Polka Dots

Simply Playful, or Cosmic & Universal?

Kusama credits herself with popularizing the polka dot, and frankly, for all she has done for the pattern, she deserves it. She became a scion of contemporary art with them. The immersive qualities of her work make it clear to any viewer, not just initiated art-insiders.

The dots make for compelling and sometimes hypnotic subjects. The simplicity of the work lends itself to other applications. While people who do not study art may not remember her name, they will most certainly recognize her work. She not only won admiration from critics and her contemporaries alike but, she has also lent her polka dots to the visual culture at large.

If you wish, you can even have a Kusama in your house. One of her silliest, most delightful series is her pumpkins. They range in size from a six-inch gourd that would sit comfortably on a desk to ones that are over six feet. Some of her pumpkins are paintings and always in black and yellow or red and white. They are a light-hearted change to an oeuvre that is often heavy.

Through collaborations with major retailers, she has been able to leave an indelible stamp on popular culture. She has worked with Louis Vuitton, a fashion house well-known for working with visual artists, including Murakami. The Murakami rainbow-bright iteration of the bags popularized by Paris Hilton is a famous example. Kusama's collaboration boasts punchy primary colors and a meandering dot pattern, modeled by Yayoi Kusama herself.

Yayoi has also worked with Lancôme (interestingly another Paris Hilton favorite) to create Juicy Tubes of lip gloss in her vibrant red. She even had a corner devoted to her art, design, and style within Bloomingdale's. Nothing says “I've made it” quite like presence at an iconic department store.

Perhaps one could speculate on the cultural significance of an artist when their work changes our perception of the ordinary material objects that surround us in our visual culture.

Almost like her lifelong friend Andy Warhol, who called our attention to the mundane materiality of a soup can, Yayoi's work resonates when everyday items like vending machines and soda cans, lip gloss tubes and parade balloons turn up with polka dots.

In 2019 Yayoi's balloon "Love Flies Up To The Sky" soared over the crowds taking in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. Not only do her effervescent bubbles shift our perception of soda cans but they draw our attention to the vending machine as well.

However, her influence extends beyond the interests of famous hotel heiresses and discerning Bloomingdale's shoppers. In 2016, she released an illustrated version of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, The Little Mermaid, in cooperation with the Louisiana Museum, in Andersen's native Denmark.

The book uses some drawings from the artist's black marker series of 2007 and some new images expressly made for the story. This book is no Disney production filled with red-headed mermaids and singing crustaceans. Instead, she leans into Andersen's original tale of Christian piety, where the young mermaid sacrifices herself so that she can have a human soul. It is also a story of infinity. The idea of everlasting life through the redemption of Christ is a story about infinity. No soul is ever lost.

Endlessness

Yayoi Kusama explores the human experience; she visits psychic depths and creates cosmic spaces for wanderers to lose track of edges and boundaries and time. There is neither end nor beginning but now. Long live the Princess of Polka Dots.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Nicole Lania is an art historian and writer who has years of experience finding genuine creativity in a world of thinly veiled reproductions. She earned a master’s degree from New York University with a focus on contemporary art and writing; her thesis was on the impact Christo’s The Gates had on the cultural capital of Central Park and the surrounding neighborhoods. She can be found walking her dog, Tucker through the New England wilderness or baking pastries in her kitchen. Nicole can be found on Instagram @nik.lania, Twitter @NicoleLania1, or her website http://www.nicolelania.com/.

Bibliography

- Kusama, Yayoi. 2020. Yayoi Kusama Exhibition. Accessed December 20, 2020. http://yayoi-kusama.jp/e/exhibitions/00.html#13.

- Nayeri, Farrah. 2012. Man-Hating Artist Kusama Covers the Tate Modern in Dots: Interview. February 12. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20120216045527/http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-02-14/man-hating-artist-kusama-covers-tate-modern-in-dots-interview.html.

- Tate Kids. n.d. Who is Yayoi Kusama. Accessed December 2020, 20. https://www.tate.org.uk/kids/explore/who-is/who-yayoi-kusama.

- Voon, Claire. 2016. Hyperallergic. August 2016. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://hyperallergic.com/316111/a-new-wave-little-mermaid-illustrated-by-yayoi-kusama/.