- Home

- / Blog

- / Art History

The Allure of Order

08/31/2022

Chaos and Order in Art History. A Story of Balance - Part II

If the disorder is not random chaos but the clash between uncoordinated orders, it follows that order is the principle, the mechanism that orchestrates trajectories. An image, whether a work of art or a real-life scene, appears orderly to our eyes when it is guided by a common design. We perceive a sense of order and harmony when we identify a structure; when the rules are clear and defined.

However, the primal impulse to order is not just a mania of control. Order is always accompanied by the desire to simplify and understand: it allows one to discern the superfluous from the indispensable and to notice similarities and differences in a complex system of facts. The psychologist Rudolph Arnheim pointed out that the need to give an aesthetic order is actually a reflection of the desire for an underlying physical, social, or cognitive balance. Just think about the social hierarchies of animals, the structure of spider webs and hives, and flower and crystal configurations. They are all fractal and symmetrical: nature is naturally ordered. It is our prerequisite for survival!

In historical moments of chaos, such as that experienced during and post-Covid pandemics - which is nothing new in human history - finding order and routine is the natural instinct to overcome the unpredictable irruption of chaos. Creating arrangements is our evolutionary strategy par excellence. The simplest and most regular form is often the winning one, in art and in life.

"Less is more"- even in art!

Art often embodied this natural tendency toward order. The over-simplification carried by Suprematism, for example, is extreme. However, the simplified design - a black square on a black background! -is not purely contemporary, having its roots in the highly stylized ornamental motifs of the geometric period of Greek Art.

Even artists, though fervent creatives attracted to chaos , felt the instinct to set themselves limits, boundaries, and a conceptual skeleton to follow on the canvas. Order is not experienced in art as a constraint, but as a step toward an appreciable coherence. It is not stillness, but a coordinated and dynamic pattern of forces.

Our capitalist and hyper-technological society taught us that evolution always proceeds from the simplest form to the most complex one. In truth, history is never so linear. In this article, we will discover five contemporary artists who demonstrate in their art practice how simplification is sometimes the most useful strategy for a full understanding of reality. Order in these paintings, sculptures, and installations becomes the goal to strive for, and art is the most suitable tool to flesh it.

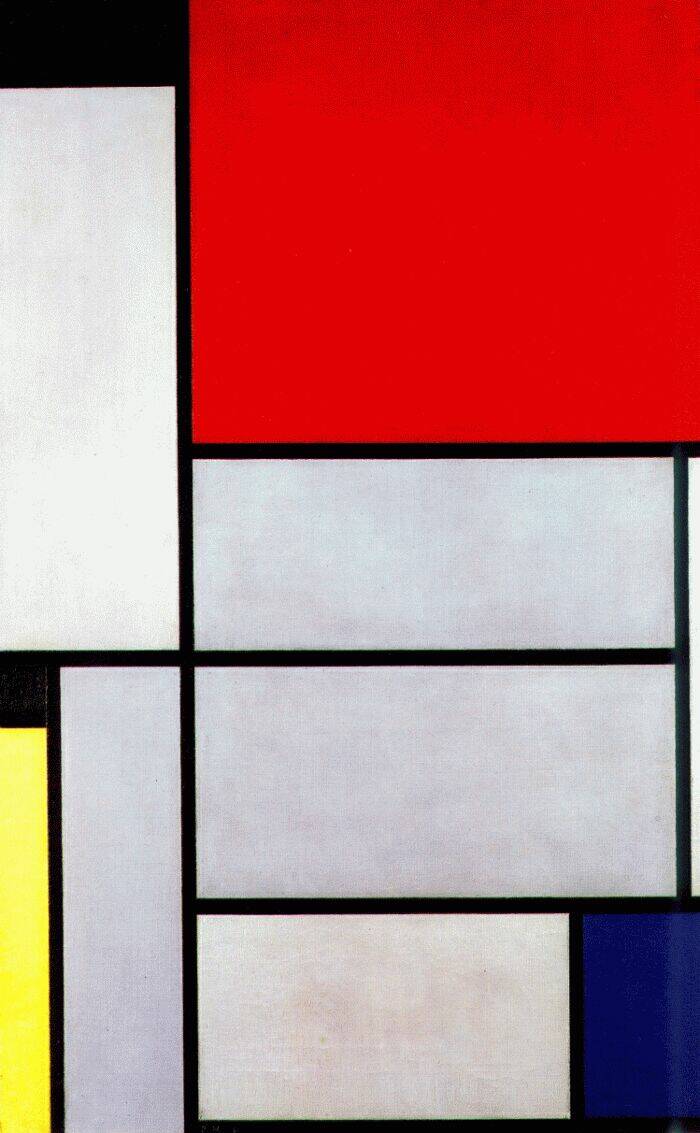

5. Schematic like a Mondrian

The order has been one of the most heartfelt inquiries of abstract painters: how to choose a composition that gives a sense of equilibrium? In the late 1920s, Piet Mondrian wondered in his writings about how to achieve a sharp, precise, and truthful painting. His style quickly became purified, revealing the natural appearance of things merely through straight lines, black and white fields, and primary colors - according to their cultural symbolism and perceptions, as discovered in previous articles about red, yellow, and blue.

However, the aseptic balance of Mondrian's painting was influenced by his forced relocation to the United States during World War II. In New York, Mondrian discovered the dynamism and freedom of a city that moved to the rhythm of the Boogie Woogie. Fascinated, he brought this movement into his orderly composition, alternating his uniform bars of color with blinking blocks of color that gave a pulsating light effect. In this way, Mondrian achieves art that is similar to jazz music: free, spontaneous, and improvisational, but not giving up balance and structure.

4. Rhythmic like Paul Klee’s Style

The rhythm and the regular cadence are aspects that also characterize the work of Paul Klee. Teacher at the Bauhaus School, the Swiss-born artist took an interest in design and architecture, combining functional vision with personal humor, an interest in music, and a fascination with the instinctive forms of childlike painting. His prolific imagination, however, is channeled into works that are far from the chaos.

In Separation in the Evening, Klee uses geometric bands of color to represent a natural phenomenon, full of nuance and wonder that is the transition from day to night. It shows through gradients all the intermediate shades of the sky, converging into a harmonious and suggestive delicate work.

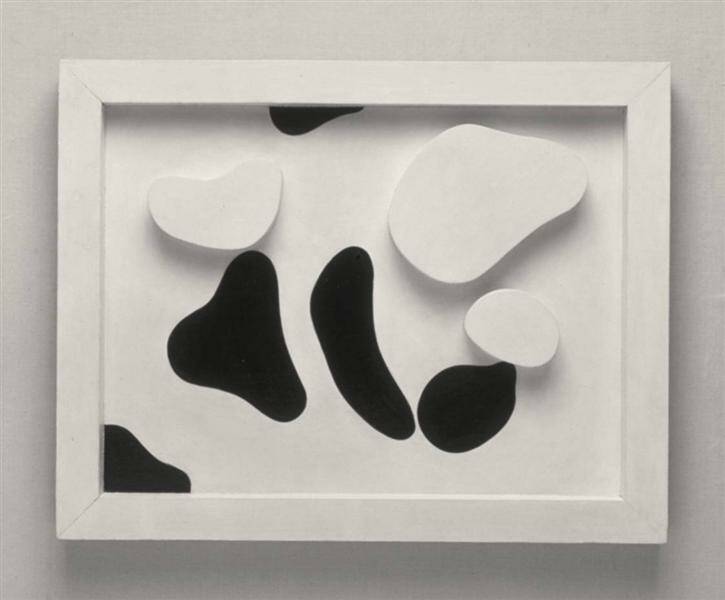

3. Controlled as Jean Arp's Shapes

The search for order unites both painters and sculptors, particularly in establishing a compositional scheme that coordinate weights and forces through forms, colors, and lines. This is evident in the series of wood reliefs and collages realized by sculptor and painter Jean Arp. The artist traces the organic forms of nature without representing them realistically. Using round shapes that evoke clouds or planets, others that refer to plants or body parts, the artist experiments with cutting out shapes from paper and then combining them on the support. Arp overlaps the laws of chance, through which he processes his shapes, and the use of human control, to create the most balanced juxtaposition.

2. Modular and Fractal as Minimal Art

Finally, if one thinks of order, the mind immediately goes to the seriality that distinguishes Minimal Art. The use of a module -a part that could be moved and recombined in different configurations- is the main feature of minimal objects of the 1960s. We can find Sol Lewitt’s open and closed cubes and Robert Morris's rearranged mirrored surfaces. However, there is also Donald Judd's more celebrated series: ten identical rectangular metal boxes ordered according to strict rules of height and distance. It's surprising that minimal artworks acquire meaning in their totality and geometric regularity.

Fibonacci, via Wikimedia Commons.

1. The Algorithm of Mario Merz

However, the master of seriality, algorithms, and light is the Italian Arte Povera artist Mario Merz. Fascinated by the number succession discovered by the medieval mathematician Fibonacci, Merz tried to put this golden principle into art. The number series represented, in fact, a progression in which each digit is the sum of the previous two. It was seen by scientists and artists as the emblem of growth in the organic world. Merz, known for his use of industrial materials such as luminous neon tubes, inserted Fibonacci's numbers in various exhibition settings, like along the spiral of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. His numbers represented a mathematical order, but that implied the laws of nature…whose beauty is anything but chaotic and random!

The artworks of these artists who try to give structure to their mental paths highlight an extremely important reflection about chaos and order: absolute chaos does not exist, there is only the possibility of recombining, distributing, and arranging elements. Energy, whether explosive like in a Pollock or ordered like in a Morris’ installation, is neither created nor destroyed, it can always be transformed. Rather than speaking of chaos and order, then, one can speak of disorder and balance; like independent paths that sometimes are coordinated under a final, complex, system.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________  Cinzia Franceschini is an Italian Art Historian specialized in History of Art Criticism, with a second degree in Communication and Sociology. She studied in Padua, Brussels, Turin and wherever you can go with the power of the Internet. She works as guide in Museum Education Departments and as a freelance writer. She writes about Contemporary Arts and Social Sciences, mostly about them at the same time, in an inclusive, feminist, transnational perspective.

Cinzia Franceschini is an Italian Art Historian specialized in History of Art Criticism, with a second degree in Communication and Sociology. She studied in Padua, Brussels, Turin and wherever you can go with the power of the Internet. She works as guide in Museum Education Departments and as a freelance writer. She writes about Contemporary Arts and Social Sciences, mostly about them at the same time, in an inclusive, feminist, transnational perspective.