- Home

- / Blog

- / Art History

Famous Still Life Paintings Last Forever In Your Mind

05/08/2021

A bouquet of flowers, a ceramic plate with colorful fruit and vegetables, a bookcase full of dusty objects, musical instruments, dishes of all kinds, freshly dressed meat … the subjects of Still Life paintings can be quite varied. Artists from all eras have tried at least once in their careers to realistically represent these themes, focusing on their colors, lights and composition. The artistic outcomes have been always different, according to the painter’s context and cultural values, but they all have something in common.

In fact, there is a valid trick to understand without fail if we are in front of a Still Life painting of any era: we can be certain that there is no trace of human beings in the canvas. The painted objects can be natural or artificial, but they are never alive. In a Still Life painting, there is no place for portraiture, human feelings, landscapes, or ordinary life scenes, only objects can be represented. Only objects can speak to us, even if motionless and in a dark room.

The complete disappearance of the human being, even if extremely interesting from a theoretical point of view and popular among artists, often places the subject of Still Life at the bottom of the hierarchy of painting genres. The Academy questioned how it was possible to exclude mankind from painting, and how art dared to focus on something banal and dead like the objects, rather than realizing, for instance, sumptuous portraits.

Still Life painting shows us that materiality is absolutely not superfluous. A focus on Still Life allows artists to explore everyday objects, portraying them as they shine with their own light, studying them under ideal conditions.

The setup of a classical Still Life painting, in fact, has great advantages but also critical issues. Because the artist can work in a controlled environment, they can choose suitable light conditions and be sure not have to portray complicated, moving, subjects. Their attention can be focused on the analysis of colors and shapes and the rendering of the composition can be as true to reality as possible.

Moreover, in Still Life painting the study of lights and shadows can be maximized, too. Through this genre, artists can explore somber atmospheres, intensify the relationship between light and darkness, as in the technique of chiaroscuro, shining light into the darkest shadows and taking care with the luminous textures revealed by carefully controlled light.

What could surprise you is that the deepest nature of this fascinating genre is already contained in its own name. The term “still life” masterfully exemplifies a life that no longer has movement or sparkle; everything is immovable or “still.” It is not life anymore, but it is not yet death. Flowers and fruits are detached from their tree and doomed to die, but the painter decides to immortalize them forever.

In this article, we will go through different ages and places and we will meet some of the most famous Still Life paintings of Art History. We will try to understand why an object of common use, no matter from what era, is still able to tell us a story. A story that reminds us of the mysterious bond between life and death, between the eternal and the ephemeral. As an aside, see below Denis' famous Homage to Cezanne, a somehow ironic study in portraiture. Ironic, because it highlights the ephemeral connections of a group of artists, ephemeral because these friends are all about to go their separate ways in life. Even more ironic, these living men are gathered around a still life, which by its nature can never go anywhere; by the act of painting the artist captured the ephemeral in immortal pigments.

Fig.3 Maurice Denis, Homage to Cezanne, 1900, via Wikiart

Caravaggio, a Basket of Fruit, and the Genesis of a Genre

The identification of the first Still Life painting of the Western World is a thorny issue. In Ancient Greece and Rome, there are still life-type scenes in frescoes and mosaics that could be identified as Still Life paintings: meat, fish and grains, baskets of figs… they preciously decorated the walls of the noble palaces. However, because these plant or food elements were always accompanied by religious symbolism, it is more frequently assumed that they are offerings to Gods or deceased loved ones.

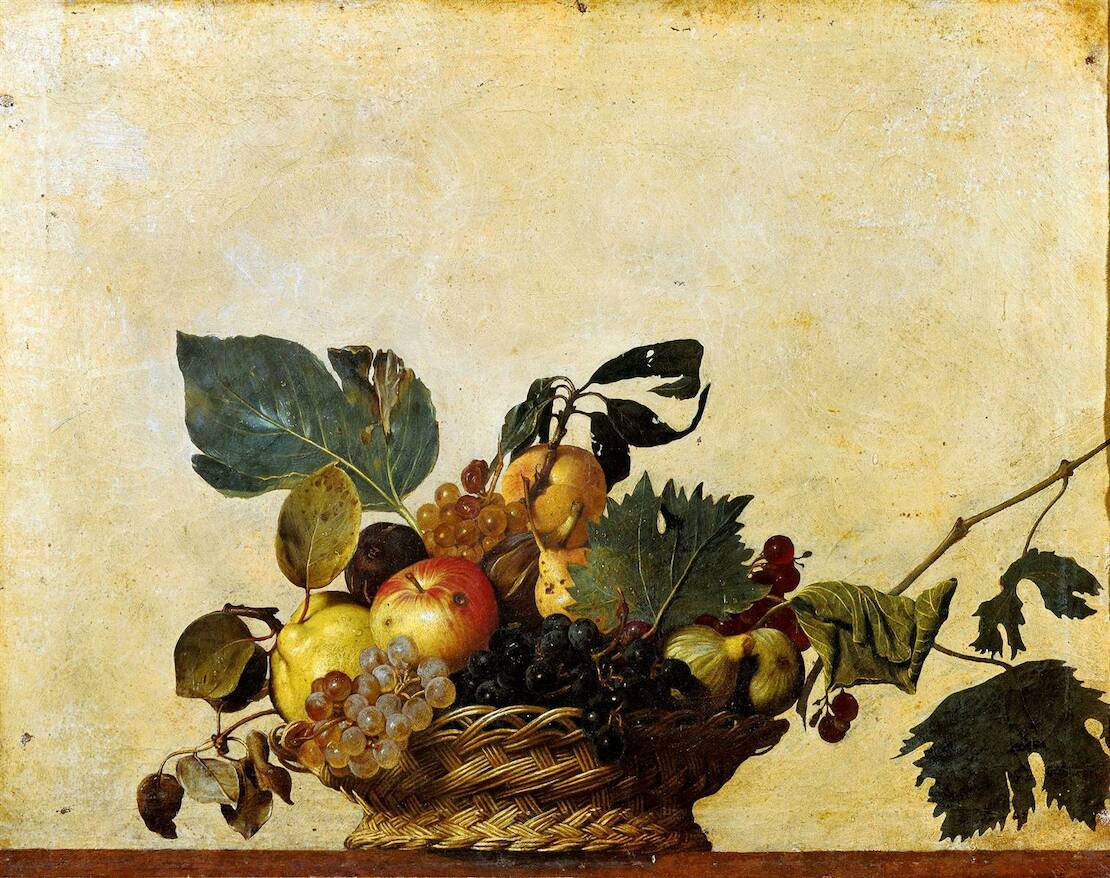

So then, when did the Still Life genre begin to exist as an autonomous art form? When did flowers and fruit start to be depicted just for what they are, and not for what they represent, not as allegories or decorations but as focused works in themselves? Caravaggio at the end of the 16th Century definitely had a hand in establishing the Still Life genre. His Basket of Fruit, now at Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan, can be considered in all rights the first Still Life masterpiece.

The fruit bowl reveals an extremely realistic rendering of each fruit; the grapes and the leaves, with their perfect volumes and lights, seem extrapolated from a photograph. However, there is a character besides the fruit still life paintings that captures our gaze: the point of view of the painting coincides with the surface, giving the composition a monumental setting. Furthermore, in this artifact Caravaggio seems to have forgotten all his iconic dark atmospheres; everything is bright and touched by the light.

Read also: 5 Ways Photographic Lighting Tells A Story

Besides Caravaggio's well-known natura morta, it is curious to highlight that another artist, contemporary of the master, experimented in the same period with Still Life subjects. The reason behind this relative lack of recognition? Fede Galizia, the artist, was a woman. Fede Galizia was one of the earliest practitioners of fruit still-lives, and her Cherries in a Silver Compote are irresistible.

Caravaggio’s Basket of Fruit and Fede Galizia’s Cherries are the classic Still Life painting par excellence; but they are also the manifestos of a cultural period. After the emphasis given to mankind during Renaissance and Humanism, artists begin again to investigate and analyze the small things. This was a seismic shift that thereafter could not be ignored.

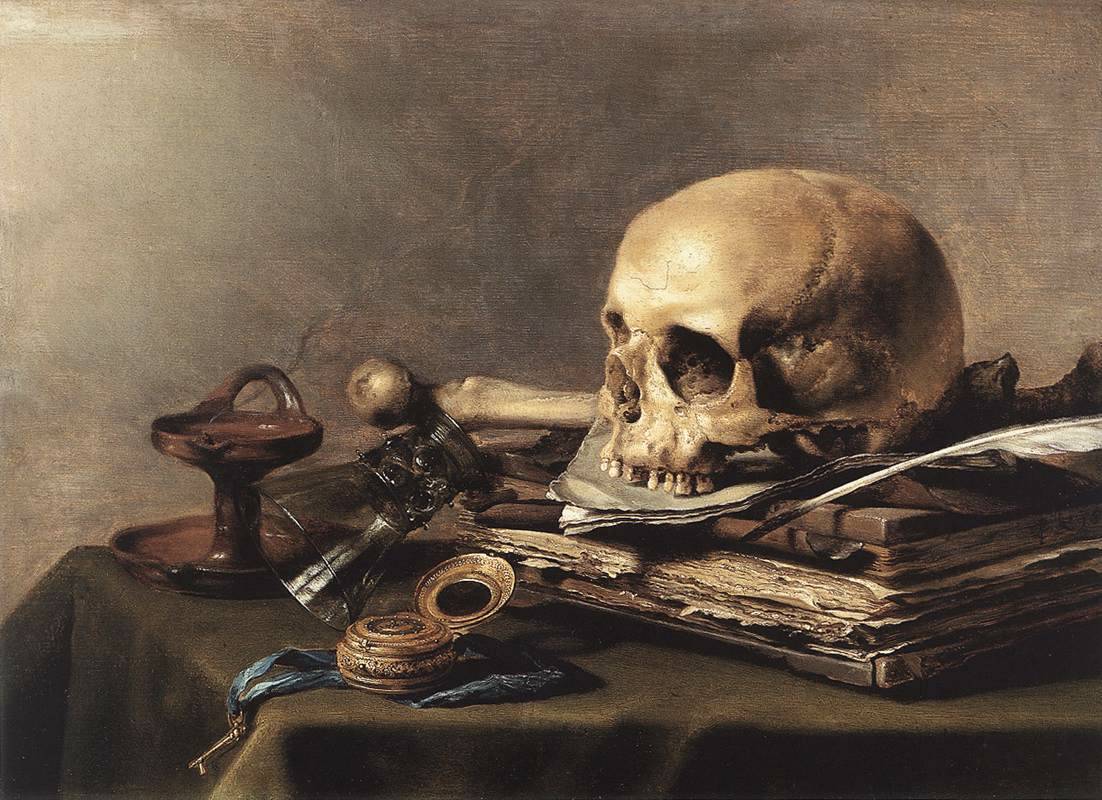

Dutch Golden Age: The Terrible Admonition of Vanitas Paintings

Caravaggio and Italian artworks were famous, but it was in Northern Europe of the 17th Century that the classic Still Life painting reached its peak of popularity. The Flemish painters were the protagonists of this period, known as the Dutch Golden Age. Their subjects included vases of flowers (mostly tulips), tables laden with cheese and meat, even, as well as dead game, both furred and feathered. In some cases, these foreboding Vanitas paintings also depicted the objects that might be commonly found in noblemen’s houses, like musical instruments, books, swords, or crystal goblets.

Flemish painters took full advantage of the qualities of their medium - oil painting; through oils, artists like Jan Brueghel, Harmen Steenwijck, or Jan Van Huysmun were able to capture the lights and shadows of the composition. Oil paint allowed the masters to depict the textures and surfaces with virtuosity. The luxurious luster of these Still Life paintings also demonstrates the bourgeois patronage of these artists.

Fig.6 Pieter Claesz, Vanitas Still Life, 1630, via Wikiart

However, Dutch painters also well knew that prosperity and wealth may not last forever. Even beauty, at a certain point, fades away. Flemish still life paintings are characterized by decadence. Even in Caravaggio’s Basket some fruits showed decay and bruising, the wormhole in the apple, but Northern painters went far beyond this allusion to death. They put in their compositions flies and other insects, cut flowers, or, even more explicitly, hourglasses and dusty skulls.

Everything in the Dutch still life compositions somehow alluded to perishing, they became a symbol of the elapse of time. This concept, called vanitas painting, reminds us of the transitory nature of our world and the brevity of our lives. Fruits and flowers of these Still Lives are not just everyday objects, they are fragile and ephemeral as soap bubbles. Aside from the grim reminder of death as a polished skull in Steenwijck's vanitas painting below (Fig 7) notice the vase, book, and ceramic pipes, precariously close to the edge of the table, poised to fall and shatter in the next moment.

Fig.7 Harmen Steenwijck, Vanitas, 1640, via Wikimedia

An Explosion of Colors by Vincent Van Gogh and Henri Matisse

The dark atmospheres of the Dutch Golden Age and their Memento Mori represents a symbolic statement for the collectivity, but Still Life painting could be also a colorful and at the same time profoundly intimate art form. This is the case of Vincent Van Gogh’s post-impressionist masterpieces: bright flower vases, created by the restless mind of the artist, to express his feelings.

The incredibly famous Sunflowers, for example, collect all the light and warmth of the South of France, where Vincent moved in search of comfort. Their three shades of yellow are the perfect colors to cheer up. Once again, in Still Life paintings, flowers are not merely flowers. They are a message of hope and vitality. And these sunflowers, as Paul Gauguin said, “were completely Vincent”, a sensitive human being who searched for all his life the light in the darkness.

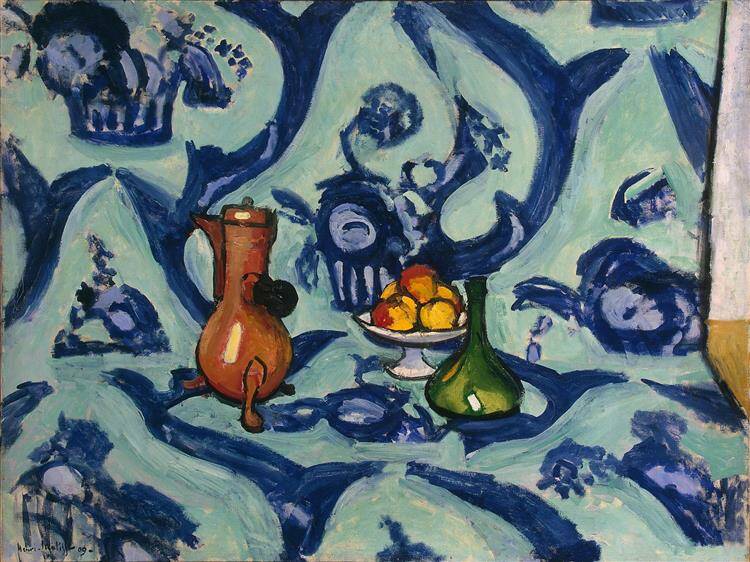

Also, Henri Matisse ventured into famous still life paintings, especially during the first phase of his career. What distinguishes his work is the powerful attention to the colors and particularly to chromatic contrasts. However, the artist's compositions are not just virtuosity in using colors and representing shapes; Matisse is interested in the emotions that these elements aroused in the viewer and in him. The interiors he chose to represent are in fact often the rooms of his property. There is always an intimate and autobiographical value in his art practice, which is also reflected in the emphasis he gave to decorate walls and tablecloths. Matisse’s decorativism makes his still life paintings so special.

Discomposing the Composition: Abstract Still Lives by Picasso

A further revolution in the representation of classic still life paintings happened with Cubism. Cézanne had already begun to perceive nature as a complex composition of geometrical planes, but it is with Picasso and Braque that abstract still life painting emerged as a genre.

Pablo Picasso started discomposing the objects, creating assemblages of different surfaces. His Still Lives are revolutionary because they challenge the idea of immobility which was typical of the genre. Thanks to the bright, vivid colors, and the sharp shapes which intersect with the background and the foreground, these paintings seem alive. There is a rhythm, a lively object that provokes the limits of the canvas.

This concept is pushed in Still Life with the Caned Chair. Inspired by his colleague Braque, Picasso started including in Still Life painting the element of collage. He put inside classic paintings pieces of industrial products, gluing and assembling them in a fascinating mixture. Doing so, he put inside a representation of everyday objects, actual everyday objects. Picasso challenged the art world simply letting reality break in, with all its revolutionary power.

Contemporary Still Lives: New Perspectives on Life and Death

Contemporary art does not exclude the genre of Still Life artworks from its research. On the contrary, a reflection on the passing of time and on the transience of things is extremely modern in our times. But how do artists of the 20th and 21st century deal with contemporary still-life paintings? Forget flower vases, fruit bowls, and oil painting, contemporaneity is capable of imagining motionless compositions, but with real objects.

A great example are the accumulations of the French artist Arman in the 60s. He filled plastic cages with recovery materials -cutlery, shoes, bottles, or gas masks. The allusion is to the classic still lives, but there is a twist: his objects are real, and they are really wasted, like garbage. The limits of the frame are the concrete borders of a box, and time really wears out these artworks, not merely ideally.

Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party is probably the best example of contemporary declinations of the still life genre. It is a massive installation, consisting of a banquet with 39 place settings, dedicated to ignored women from history. Each table place has its own runners, plates, utensils. It is probably the most extreme evolution of the still life genre, which defies the conventions of a centuries-old, male-centered, artistic tradition.

Of course, Still Lives are also one of the favorite subjects of contemporary photographers, being able to experiment with arrangement, lighting, and composition.

What we can understand from Still Lives is that they are never just aesthetic compositions of light and colors. They represent something that once upon a time was alive, but once detached from the tree it is destined to perish or consumed. However, what makes these ephemeral objects immortal is the artist. Still, lives are not only analytical virtuosity, they are first of all still artworks; frozen moments that tell us something about the cycle of nature and the eternity of art.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Cinzia Franceschini is an Italian Art Historian specialized in the History of Art Criticism, with a second degree in Communication and Sociology. She studied in Padua, Brussels, Turin, and wherever you can go with the power of the Internet. She works as a guide in Museum Education Departments and as a freelance writer. She writes about Contemporary Arts and Social Sciences, mostly about them at the same time, in an inclusive, feminist, transnational perspective.

Cinzia Franceschini is an Italian Art Historian specialized in the History of Art Criticism, with a second degree in Communication and Sociology. She studied in Padua, Brussels, Turin, and wherever you can go with the power of the Internet. She works as a guide in Museum Education Departments and as a freelance writer. She writes about Contemporary Arts and Social Sciences, mostly about them at the same time, in an inclusive, feminist, transnational perspective.