- Home

- / Blog

- / Art History

Caravaggio's Untold Secrets

12/13/2020

Chalk portrait of Caravaggio by Ottavio Leoni circa 1691

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was a fine example of life imitating art; his star rose nearly as quickly as it fell during the Baroque Period. The artist moved to Rome in 1592. By 1595, Cardinal Francesco del Monte recognized his genius, which stimulated prestigious commissions. His notoriety and meteoric rise to fame also lead to his rapid demise. By 1606 he was on the run with a price on his head for murder, and by 1610, he was dead. His masterful use of light left an enduring legacy despite his short life.

Caravaggio Rose From Backwater Obscurity

Not all artists are born in big cities; perhaps most are not. As you can see from the chalk drawing of the artist as a young man by Ottavio Leoni c. 1621 (via Wikimedia Commons), perhaps Caravaggio was like artistic kids of today, who gravitate to the city and wait on tables, work in construction, or tend bar, basically determined to fake it until they make it as an artist. Before his breakthrough in 1595, Caravaggio hawked art on the streets of Rome. It was not until the Church took an interest in his talent that his oeuvre developed to mythic levels.

A narrative thread connects Caravaggio’s life to Saint Matthew—whose life Caravaggio depicted at different stages in several of his most lauded paintings. Both the saint and the artist who portrayed him emerged from near obscurity and both men had their fair share of vices, yet the study of light demanded their complete attention.

After dashing off masterpiece oil paintings, Caravaggio would celebrate for days. His carousing became not just a nuisance but violent. He killed two men as a result. St. Matthew began his life as a tax collector and sometimes gambler but found salvation through light. The light caused the demise and subsequent veneration of two men that appeared to be on separate paths. Baroque artists captured the tension of a changing world and shed light on details once forgotten.

Caravaggio Channeled Baroque Religiosity in Dark & Light

Artists who channel the zeitgeist of their era have an impact because they touch a nerve; their work speaks truth to the viewer. That’s how art works. The casual viewer of Baroque art may find themselves wondering if every painting is going to be religiously inclined. The short answer is yes. The broader context of Caravaggio’s dramatic rise and fall reveals a backdrop of dogmatic struggle that also played out. The Italian Renaissance appealed most to the intelligentsia. A shift occurred across subject matter but also technique. Botticelli’s contrapposto babes, standing in dappled sunshine, wrapped in diaphanous silks such as those found in La Primavera, were commonplace in Italian Renaissance art. In the context of moral reckoning, Baroque painting required more gravitas and fewer see-through outfits.

|

Sandro Botticelli, La Primavera, 1477-1482 via WikiArt |

Meanwhile, with its heavy-handed religiosity, the Baroque period reflects the powerful efforts of upper echelons of spiritual power like Popes, Cardinals, and Bishops to regain control of the conversation. The Baroque thesis emphasizes the Catholic Church's power and wealth in the face of outside pressure such as Protestant reformation. Baroque art also channels a starkly different moral imperative from the Renaissance, which focused on the revival of knowledge for the sake of learning. In 1972’s Ways of Seeing, John Berger points out the importance of genre paintings, depicting subject matter and scenes from everyday life. It matters which subjects strike interest in a given moment. The shift away from classical, mythological, imagery underscores the importance of the religious subject matter in the Baroque era.

Little overtly religious genre painting exists from Protestant sources. Jesus was still theologically the star-of-the-show, but his depiction was not essential. The Protestant faith chose a path of simplicity rather than focus on religious symbolism, metaphor, sacraments, and idolatry. The difference between walls in a highly decorated Catholic church and an austere Protestant church speaks volumes.

Caravaggio Channeled Inspiration from Other Artists

Artists have repackaged ideas for centuries. Newness is all in the approach. Art does not exist in a vacuum, and even as styles change, details endure from subsequent movements. Enter chiaroscuro, a technique that saw its pinnacle in the Baroque era. Despite this, it was nothing revolutionary to its time. The chiaroscuro technique has its origins in printmaking and was used to describe the contrast created using separate woodcuts: light and dark. Caravaggio and his contemporaries took the style across the boundaries of printing. It was used in painting as well, notably to the success of Caravaggio.

|

Hans Holbein, Resting Christ, 1519 via Wikimedia Commons |

|

In Rembrandt's Christ's Crucifixion one can see a similar synthesis of style. Within this work, a smattering of stylistic techniques is visible. Rembrandt draws the viewers’ attention to the central narrative of Christ’s death, all through light. Christ's central position is also vital to establishing focus. Below Jesus, one can make out Roman soldiers. The Marys mourn at his feet, and the rest of the scene remains in shadow. Rembrandt references German Expressionism The secondary characters in the drypoint print are twisted and grotesque, representative of sin. It is impossible not to draw a parallel between the spill of light seen in Rembrandt’s work and Caravaggio. Rembrandt, The Three Crosses, 1653 via Google Cultural Institute |

The influences on these two artists are evident. All art is in conversation with art historical predecessors. Artworks may question ideas but cannot divorce themselves entirely from the concept of precedent. Caravaggio's influence made its signature in centuries of visual culture.

Caravaggio’s Early Genre Paintings Influenced His Later Work

Genre painting subject matter may repeat, but no two images are telling the same story. The differences are conspicuous when laid bare in the evolution of Caravaggio’s style. When he first came to Rome and was hawking his art in the streets, Caravaggio painted typical genre subjects like the Cardsharps (circa 1594).

|

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, circa 1594, courtesy of Wikipedia |

Caravaggio’s emerging style is easy to see here; later his religious works retained that sense of a real-life moment, a captured present, although the subject was now a saint. Unlike other religious subjects, the disciples exist as imperfect figures. Their stories are built from real-life moments when spiritual intervention occurred. Saints and disciples reflect the flaws of humanity within themselves. Therefore, St. Matthew makes a compelling subject, even notwithstanding his unique connections to Caravaggio. St. Matthew is neither prophet nor an angel. He is quite notably a sinner who sins egregiously. Christ calls to Matthew at the custom-house while Matthew counts taxes. Usury is a major biblical no-no. Matthew distinguishes himself from the other evangelists through his sins.

St. Matthew does not possess the sweetness of St. Luke, the designs for the apocalypse of St. John, or the austerity of St. Mark. These differences become apparent in the writings of the gospel. Luke comes across as the platonic form of an evangelist; his reports are sweet and innocent. John tempers this with mystical qualities to his writings, most notably his depiction of Christ's second coming. Mark is the straight man; he lionizes the works of Christ. Matthew has the most important role, adding in the shades of gray. When faced with Christ, Matthew follows without question; his humanity connects him to the light.

|

Caravaggio, The Calling of St. Matthew, 1599-1600 via WikiArt. |

Caravaggio Humanizes The Struggles of St. Matthew

The study of Caravaggio’s depiction of St. Matthew provides a window into the artist’s world. Matthew is notably cast into the light in these pictures and psychically observed. Typically, religious painting focuses on Christ as a subject. Uniquely, this painting focuses more on Matthew. Jesus barely peeks out from the shadows. Light plays an active role in the narrative of St. Matthew, developed by Caravaggio. Caravaggio’s rendering of The Calling of St. Matthew is as visually striking as it is intellectually fascinating. The left of the canvas is entirely in shadow, whereas the upper right window lets in a bright flood of light. With the sunshine comes Christ accompanied by Saint Peter, who is only subtly visible in the flood of brilliant light. It takes close inspection to see a fragile golden halo above Christ's head. The light and shadow meet in the middle of the table where St. Matthew sits stacking coins. Debate still looms over which figure is St. Matthew. Many scholars suspect it is the bearded man pointing as if to say, "who, me?". Others wonder if it might be a younger man who the bearded figure points at the head of the table, which is Matthew.

The painting’s ambiguity still confounds art historians. Although, it is almost unimportant in contrast to the use of light. The light is so bright it is almost blinding. It may obscure the issue of identity entirely. A potent metaphor for the interaction with brilliance establishes itself on the canvas. It is so powerful that it overtakes the subject and adds confusion.

|

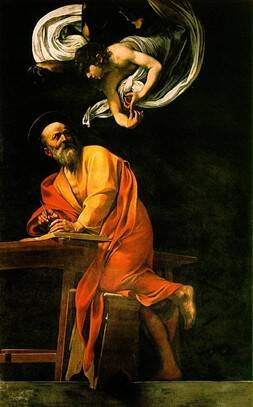

The two following paintings: The Inspiration of St. Matthew and The Martyrdom of St. Matthew, complete a narrative loop and the depiction as mentioned earlier of the calling. The Inspiration of St. Matthew depicts the familiar bearded figure, who this time bathed in divine light. He perches at a desk and now dons a thin halo. The model looks disturbed and contorted. Like he is thwarted by his knowledge. Coming from the background is an angel, whispering the gospel into Matthew’s ear. The deep shadow is less dramatic in this image. The saint stands alone against a dark background. The light, however, drives the narrative. |

Light makes the Evangelist seem to pop off the canvas. This iteration of Matthew is different. His person stands out clearly and is no longer shrouded in the shadows. There is no hiding from the truth of Christ's word.

The Martyrdom of St. Matthew is a hallmark of subtle chiaroscuro painting. Matthew's inspiration comes across as bold by comparison. Being a person of faith and preaching the word of God so openly can be regarded as dangerous. Caravaggio is more subtle in his usage of light in this work because the risk of faith puts a damper on the saint's life. Matthew's figure again becomes obscured in shadow, as his assailant has won and takes in the light. The light of God no longer blinds or disturbs him, but to what end?

|

Caravaggio patron, Cardinal Francesco del Monte, was particular in how he wanted the saint’s death depicted. True to Caravaggio’s style, this depiction was narrative. The light highlights the critical parts of the story. It is almost cinematic. An angel sits in the upper right corner of the canvas, looking down upon the gruesome scene. St. Matthew lies supine at center stage, where a soldier is attacking him. Bright light focuses on the assailant, not St. Matthew. In the distance, a shadowy king figure in yellow colors stands looking onto the scene. At the king’s behest, St. Matthew dies for preaching God’s word. Light acts as both metaphor and storyteller in the St. Matthew cycle. It is a uniquely Baroque perspective that admirably takes on the power of faith. Caravaggio, The Martyrdom of St. Matthew 1599-1600 via WikiArt |

Caravaggio Pointed the Way To Modern Drama

Baroque painting compels viewers to this day. Perhaps the popularity is owed to the clarity the light manifests. There is no question of subject matter or narrative with works of Baroque art. Light speaks for itself. The way the light tells a story comes across as a nod to the motion picture—an invention that wouldn't be developed until centuries later. The harsh lighting, typical of Caravaggio's style, is modern. The stylistic choices of the era made an indelible mark on visual storytelling.`

Carravagio’s depictions of St. Matthew found a final resting place at San Luigi del Francesci, Rome, in the Coscarelli Chapel. When viewed together, the paintings come across like a soap opera, complete with a similar lighting scheme. Protagonists pop forward from obscurity, and supporting characters peek faintly out of the woodwork. Indeed, Alexis Carrington or Erica Kane could easily find themselves scheming in the shadows these paintings offer. The Caravaggio lighting style fits perfectly into the aim of the soap operas.

Drama, danger, and deception have always been a part of human history. Trapping these uncontrollable realities inside the television or a canvas allows the viewer to explore risk without consequence. In the cavernous chapel, it is impossible not to see the light Caravaggio captures. It appears to reflect internally from the canvas.

Or perhaps the brightness came from directly from Caravaggio’s genius. Caravaggio makes a fascinating argument for adjusting perspectives to familiar stories. New truths exist in unexplored corners. Caravaggio's Matthew cycle remains a crucial example. What he chose to reveal or hide with light belied a nuanced tale of struggle and redemption.

Nicole Lania is an art historian and writer who has years of experience finding genuine creativity in a world of thinly veiled reproductions. She earned a master’s degree from New York University with a focus on contemporary art and writing; her thesis was on the impact Christo’s The Gates had on the cultural capital of Central Park and the surrounding neighborhoods. She can be found walking her dog, Tucker through the New England wilderness or baking pastries in her kitchen. Nicole can be found on Instagram @nik.lania, Twitter @NicoleLania1, or her website www.nicolelania.com

Caravaggio took inspiration from northern European printmakers and painters such as Hans Holbein, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt, who pioneered contrasting concepts in their respective works.

Caravaggio took inspiration from northern European printmakers and painters such as Hans Holbein, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt, who pioneered contrasting concepts in their respective works.

Accepting otherworldly intelligence will always be a burden, whether it is coming to grips with the Messiah as Matthew does, or making peace with a brilliant but manic mind in the case of Caravaggio. Perhaps Caravaggio found success in this period because he was the owner of a brain that already operated in extremes.

Accepting otherworldly intelligence will always be a burden, whether it is coming to grips with the Messiah as Matthew does, or making peace with a brilliant but manic mind in the case of Caravaggio. Perhaps Caravaggio found success in this period because he was the owner of a brain that already operated in extremes.